Turbopack Performance Benchmarks

Monday, October 31st, 2022

Summary

- We are thankful for the work of the entire OSS ecosystem and the incredible interest and reception from the Turbopack release. We look forward to continuing our collaboration with and integration into the broader Web ecosystem of tooling and frameworks.

- In this article, you will find our methodology and documentation supporting the benchmarks that show Turbopack is much faster than existing non-incremental approaches.

- Turbopack and Next.js 13.0.1 are out addressing a regression that snuck in prior to public release and after the initial benchmarks were taken. We also fixed an incorrect rounding bug on our website (

0.01s→15ms). We appreciate Evan You's work that helped us identify and correct this. - We are excited to continue to evolve the incremental build architecture of Turbopack. We believe that there are still significant performance wins on the table.

At Next.js Conf, we announced our latest open-source project: Turbopack, an incremental bundler and build system optimized for JavaScript and TypeScript, written in Rust.

The project began as an exploration to improve webpack’s performance and create ways for it to more easily integrate with tooling moving forward. In doing so, the team realized that a greater effort was necessary. While we saw opportunities for better performance, the premise of a new architecture that could scale to the largest projects in the world was inspiring.

In this post, we will explore why Turbopack is so fast, how its incremental engine works, and benchmark it against existing approaches.

Why is Turbopack blazing fast?

Turbopack’s speed comes from its incremental computation engine. Similar to trends we have seen in frontend state libraries, computational work is split into reactive functions that enable Turbopack to apply updates to an existing compilation without going through a full graph recomputation and bundling lifecycle.

This does not work like traditional caching where you look up a result from a cache before an operation and then decide whether or not to use it. That would be too slow.

Instead, Turbopack skips work altogether for cached results and only recomputes affected parts of its internal dependency graph of functions. This makes updates independent of the size of the whole compilation, and eliminates the usual overhead of traditional caching.

Benchmarking Turbopack, webpack, and Vite

We created a test generator that makes an application with a variable amount of modules to benchmark cold startup and file updating tasks. This generated app includes entries for these tools:

- Next.js 11

- Next.js 12

- Next.js 13 with Turbopack (13.0.1)

- Vite (4.0.2)

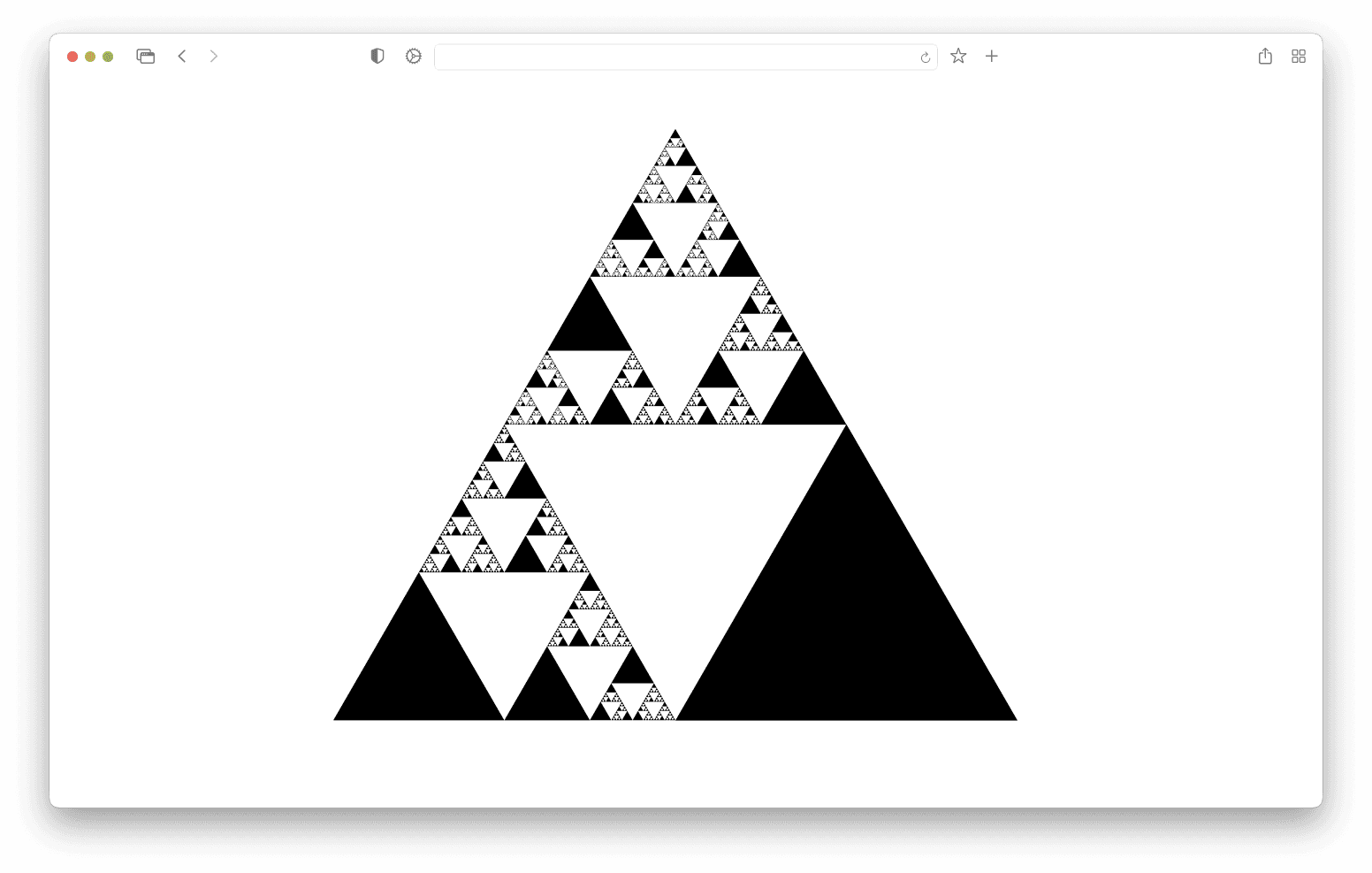

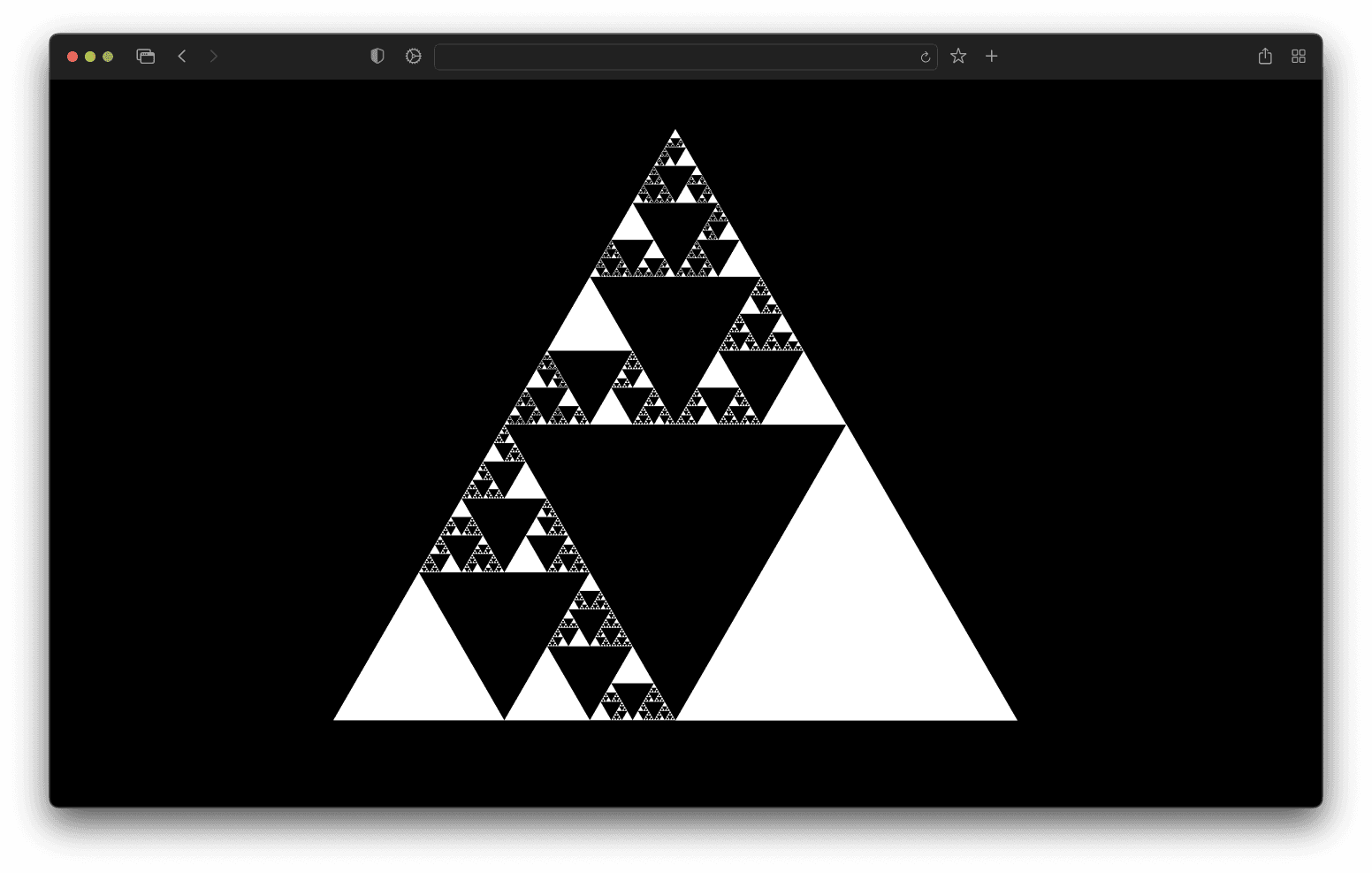

As the current state of the art, we are including Vite along with webpack-based Next.js solutions. All of these toolchains point to the same generated component tree, assembling a Sierpiński triangle in the browser, where every triangle is a separate module.

Cold startup time

This test measures how fast a local development server starts up on an application of various sizes. We measure this as the time from startup (without cache) until the app is rendered in the browser. We do not wait for the app to be interactive or hydrated in the browser for this dataset.

Based on feedback and collaboration with the Vite team, we used the SWC plugin with Vite in replacement for the default Babel plugin for improved performance in this benchmark.

Data

To run this benchmark yourself, clone vercel/turbo and then use this command from the root:

Here are the numbers we were able to produce on a 16” MacBook Pro 2021, M1 Max, 32GB RAM, macOS 13.0.1 (22A400):

File updates (HMR)

We also measure how quickly the development server works from when an update is applied to a source file to when the corresponding change is re-rendered in the browser.

For Hot Module Reloading (HMR) benchmarks, we first start the dev server on a fresh installation with the test application. We wait for the HMR server to boot up by running updates until one succeeds. We then run ten changes to warm up the tooling. This step is important as it prevents discrepancies that can arise with cold processes.

Once our tooling is warmed up, we run a series of updates to a list of modules within the test application. Modules are sampled randomly with a distribution that ensures we test a uniform number of modules per module depth. The depth of a module is its distance from the entry module in the dependency graph. For instance, if the entry module A imports module B, which imports modules C and D, the depth of the entry module A will be 0, that of module B will be 1, and that of modules C and D will be 2. Modules A and B will have an equal probability of being sampled, but modules C and D will only have half the probability of being sampled.

We report the linear regression slope of the data points as the target metric. This is an estimate of the average time it takes for the tooling to apply an update to the application.

The takeaway: Turbopack performance is a function of the size of an update, not the size of an application.

Data

To run this benchmark yourself, clone vercel/turbo and then use this command from the root:

Here are the numbers we were able to produce on a 16” MacBook Pro 2021, M1 Max, 32GB RAM, macOS 13.0.1 (22A400):

As a reminder, Vite is using the official SWC plugin for these benchmarks, which is not the default configuration.

Visit the Turbopack benchmark documentation to run the benchmarks yourself. If you have questions about the benchmark, please open an issue on GitHub.

The future of the open-source Web

Our team has taken the lessons from 10 years of webpack, combined with the innovations in incremental computation from Turborepo and Google's Bazel, and created an architecture ready to support the coming decades of computing.

Our goal is to create a system of open source tooling that helps to build the future of the Web—powered by Turbopack. We are creating a reusable piece of architecture that will make both development and warm production builds faster for everyone.

For Turbopack’s alpha, we are including it in Next.js 13. But, in time, we hope that Turbopack will power other frameworks and builders as a seamless, low-level, incremental engine to build great developer experiences with.

We look forward to being a part of the community bringing developers better tooling so that they can continue to deliver better experiences to end users. If you would like to learn more about Turbopack benchmarks, visit turbo.build. To try out Turbopack in Next.js 13, visit nextjs.org.

Update (2022/12/22)

When we first released Turbopack, we made some claims about its performance relative to previous Next.js versions (11 and 12), and relative to Vite. These numbers were computed with our benchmark suite, which was publicly available on the turbo repository, but we hadn’t written up much about them, nor had we provided clear instructions on how to run them.

After collaborating with Vite’s core contributor Evan You, we released this blog post explaining our methodology and we updated our website to provide instructions on how to run the benchmarks.

Based on the outcome of our collaboration with Vite, here are some clarifications we have made to the benchmarks above on our testing methodology:

Raw HMR vs. React Refresh

In the numbers we initially published, we were measuring the time between a file change and the update being run in the browser, but not the time it takes for React Refresh to re-render the update (hmr_to_eval).

We had another benchmark which included React Refresh (hmr_to_commit) which we elected not to use because we thought it mostly accounted for React overhead—an additional 30ms. However, this assumption turned out to be wrong, and the issue was within Next.js’ update handling code.

On the other hand, Vite’s hmr_to_eval and hmr_to_commit numbers were much closer together (no 30ms difference), and this brought up suspicion that our benchmark methodology was flawed and that we weren’t measuring the right thing.

This blog post has been updated to include React Refresh numbers.

Root vs. Leaf

Evan You’s benchmark application is composed of a single, very large file with a thousand imports, and a thousand very small files. The shape of our benchmark is different – it represents a tree of files, with each file importing 0 or 3 other files, trying to mimic an average application. Evan helped us find a regression when editing large, root files in his benchmark. The cause for this was quickly identified and fixed by Tobias and was released in Next 13.0.1.

We have adapted our HMR benchmarks to samples modules uniformly at all depths, and we have updated this blog post and our documentation to include more details about this process.

SWC vs. Babel

When we initially released the benchmarks, we were using the official Vite React plugin which uses Babel under the hood. Turbopack itself uses SWC, which is much faster than Babel. Evan You suggested that for a more accurate comparison, we should change Vite’s benchmark to use the SWC plugin instead of the default Babel experience.

While SWC does improve Vite’s startup performance significantly, it only shows a small difference in HMR updates (<10%). It should be noted that the React Refresh implementations between the plugins are different, hence this might not be measuring SWC’s effect but some other implementation detail.

We have updated our benchmarks to run Vite with the official SWC plugin.

File Watcher Differences

Every OS provide its own APIs for watching files. On macOS, Turbopack uses FSEvents, which have shown to have ~12ms latency for reporting updates. We have considered using kqueue instead, which has much lower latency. However, since it is not a drop-in replacement, and brings its lot of drawbacks, this is still in the exploratory stage and not a priority.

Expect to see different numbers on Linux, where inotify is the standard monitoring mechanism.

Improving our Methodology

Our benchmarks originally only sampled 1 HMR update from 10 different instances of each bundler running in isolation, for a total of 10 sampled updates, and reported the mean time. Before sampling each update, bundler instances were warmed up by running 5 updates.

Sampling so few updates meant high variance from one measurement to the next, and this was particularly significant in Vite’s HMR benchmark, where single updates could take anywhere between 80 and 300ms.

We have since refactored our benchmarking architecture to measure a variable number of updates per bundler instance, which results in anywhere between 400 and 4000 sampled updates per bundler. We have also increased the number of warmup updates to 10.

Finally, instead of measuring the mean of all samples, we are measuring the slope of the linear regression line.

This change has improved the soundness of our results. It also brings Vite’s numbers down to an almost constant 100ms at any application size, while we were previously measuring 200+ms updates for larger applications of over 10,000 modules.

Conclusion

We are now measuring Turbopack to be consistently 5x faster than Vite for HMR, over all application sizes, after collaborating with the Vite team on the benchmarks. We have updated all of our benchmarks to reflect our new methodology.